Palestinian visual artists have consistently used their art as instruments of political resistance and cultural survival. Whether living under the severe restrictions and brutal manipulations of an extended colonial military occupation, or drifting in the constant uncertainties of exile, the great majority of Palestinian visual artists have taken up the cause of liberation, as well as the experiences of displacement and occupation, as the central themes of their work.

Over the course of four generations, the visual arts of Palestine have burst into life like germinating seeds that had been widely scattered after pounding storms. With a sense of tremendous creative urgency, Palestinian artists have flourished under very difficult conditions and have consistently presented the severe existential threats facing Palestinian culture. When surveying the development of Palestinian visual arts since the start of the Nakba, one quickly discovers that the arts of Palestine represent a turbulent and ever shifting landscape of survival and resistance. This landscape embodies the hopes and fears of a people struggling against the crushing mechanisms of an ongoing cultural genocide. The creative output of Palestinian artists has varied in its sources of influence and forms of expression. Post-1948 Palestinian visual art has ranged from the propagandistic to the nostalgic, from the expressive to the conceptual and from time-based performative works to metaphorical realism. Themes of loss, resistance, return, and rebirth have been poetically, if not always critically, expressed by four generations of Palestinian artists.

Inside the nascent and still mostly under-recognized contemporary Palestinian art scene, artists have generously supported each other and have jealously competed with each other. They have liberally shared ideas with other artists and covetously stolen ideas from fellow artists. Until the Internet became widely available in Palestine, the restrictions of the military-colonial occupation had shaped a constricted and relatively insular art culture. Within that culture, Palestinian artists learned a great deal from one another, but did not always acknowledge their sources of edification. Driven by a need for collaboration and an instinct for competition, Palestinian artists have often presented a façade of unity that disguised cliquish alliances.

As a result of the ever shifting Palestinian cultural landscape of competition and collaboration, a range of important questions quickly arise when a young Palestinian artist creates an ambitious body of work that directly references the images and ideas of an esteemed older Palestinian artist. The art community can reasonably question whether or not this new body of work is an under-handed pilfering of iconic images? They can justly wonder if the young artist’s effort is a calculated journey to temporary fame on the coattails of a revered artist? They may be fair in their suspicion that the striking new paintings are an all-too-easy adaptation of familiar and cherished images, by an emerging artist who is part of a generation that has been suckled at the breast of digital media and gratuitous appropriation. Alternatively, the perceptive viewer may wonder if, in creating a body of work that directly references the artwork of a senior artist, the younger artist has embarked on a challenging intellectual undertaking that could force the art community, if not the nation, to critically reassess the lasting cultural and political meaning of iconic works of art.

[Bashar Khalaf, Shadow of a Shadow (2015-2016). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

[Bashar Khalaf, Shadow of a Shadow (2015-2016). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

Bashar Khalaf’s new paintings for the series Shadow of the Shadow can be seen as homage to the renowned Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour. They are in large part an admiring elegy to Mansour’s massive influence on contemporary Palestinian art. However, Khalaf’s paintings must also be considered as a declaration of independence from the work of an iconic master and his influence on a generation of visual artists.

Khalaf and Mansour’s paintings reflect on themes of occupation, loss, and political responsibilities from distinctly different vantage points. The unique perspectives presented by each artist have been shaped by the political and cultural experiences of their respective generations. Bashar Khalaf (born 1991) studied under Sliman Mansour (born 1947) at Al Quds University. Khalaf is a great admirer of his mentor’s technical sophistication, his nuanced narrative structures, his compositional arrangements, his penetrating cultural critiques, and his life long commitment to the struggle of the Palestinians against an extremely divisive occupation. Like Sliman Mansour, Bashar Khalaf’s paintings are thoughtfully composed, sensitively painted and are imbued with political metaphors. However, Khalaf’s paintings are deliberately sparing and bare in their compositional structures, and address the viewer with less overt symbolism than Mansour’s works.

Through their austere representation of forms and space, Khalaf’s paintings present a cultural critique of his generation’s relationships with the experiences of occupation and resistance. His new paintings reflect on the present realities of Palestinian politics, while underscoring the evolution and deterioration of the political conditions of the Palestinians under the past forty-five years of occupation.

The themes in Khalaf’s new paintings are identical to the themes presented in Sliman Mansour’s artwork. Both artists offer a visual meditation on the experience of life under occupation, as well as on the personal and collective responsibilities of the occupied. Khalaf directly references Mansour’s paintings without appropriating any of his mentor’s compositions and cultural commentary. Instead, he consciously positions his assessment of their shared political themes from the perspective of a young Palestinian artist living in an increasingly vanishing homeland. Khalaf is well aware of the weight of history that has been placed on the shoulders of his generation, but is also cognizant of the increasingly insurmountable limitations to change the course of that history. Khalaf’s paintings investigate the tension between the sense of national responsibilities and the paralyzing restrictions that has been created by the ongoing military occupation on generations of Palestinians. Bashar Khalaf’s paintings identify the uncomfortable realities of his generation and suggest that between the desire for resistance and the ostensible futility of direct action lays a paralyzing, albeit seductive, acceptance of the status quo. This seduction is amplified by the relative comfort of materialism, and the involuntary personal and cultural adjustments to the now seemingly routine diet of enclosures, land appropriations, violence, and humiliation, provided by the occupation.

By critically questioning the viewers’ and the artist’s relationships to the settler-colonial military occupation, Khalaf’s paintings offer real-time warnings to generations of Palestinians that have known nothing but the restraints of that occupation. In subtle, seductive, and yet uncomfortable ways, Khalaf’s artwork highlights the dangers of confusing inertia for action, passivity for resistance and division for strength.

[Sliman Mansour, Bride of the Homeland (1976). Image copyright the artist.]

[Sliman Mansour, Bride of the Homeland (1976). Image copyright the artist.]

[Bashar Khalaf, Bride of the Homeland (2015). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist.]

[Bashar Khalaf, Bride of the Homeland (2015). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the artist.]

All of Bashar Khalaf’s paintings in this exhibit leave the viewer with troubling questions. The painting that I found to be the most seductive in its simplicity and beauty, yet most disturbing in the questions it raises, depicts a girl’s school uniform that has been neatly hung on a wooden hanger and carefully displayed on a red string in front of a solid black ground. Khalaf’s painting of the school uniform references Sliman Mansour’s 1976 painting The Bride of the Homeland. In that painting, Mansour beautifully represented the lifeless body of Lena Nabulsi, dressed in her school uniform, lying in a foreshortened headfirst perspective with a small puddle of blood under her head. A small, embroidered Palestinian flag and a heart shaped gold locket appear on the right side of her chest. Sliman Mansour painted The Bride of the Homeland when he was twenty-nine years old, as a response to the first recorded murder of a Palestinian schoolgirl by an Israeli soldier. Mansour’s elegantly choreographed body of Lena Nabulsi is reminiscent of the tragic beauty employed in the Mannerist paintings of Catholic martyrs. By referencing that style, Mansour suggests that the young girl’s senseless slaughter transcends national suffering and equates her death with the burdens of religious sacrifice.

In the culture of Palestinian resistance, Sliman Mansour’s painting of Lena Nabulsi instantly became, and still remains, an iconic image of heroic martyrdom, sacred struggle against injustice, as well as a lament against the senseless killing of children by the Israeli occupation forces. In his visual commentary on Mansour’s eloquent allegory of heroic national sacrifice, Khalaf removed the figure from the crime scene and completely reconfigured the pictorial space. Only a neatly displayed school uniform remains in the painting as the sole reference to Nabulsi’s tragic death. The removal of Lena Nabulsi’s body from the painting raises numerous troubling questions about the viewer’s relationship to the concept and history of martyrdom in cultures of revolutionary resistance.

From my vantage point, the culture of martyrdom cherishes individual sacrifice while forgetting the sacrificed individual. It reduces the dead to two-dimensional icons of nobility by simplistically glorifying the “martyr” and simultaneously denying the complexity of that individual’s life. In the forty years since the brutal and senseless slaughter of Lena Nabulsi, countless Palestinian children have lost their lives to the cruel violence of the occupation. But who can name those “martyred” children? Who can name their brothers and sisters, or the mothers and fathers, who still mourn and miss them? Khalaf’s empty uniform, hanging neatly from a red string in a non-space that is deliberately devoid of life, leaves room for future children to be tragically draped in the metaphorical robe of martyrdom. The painting compels me to reflect on our responsibilities to the dead and the dying children, as well as to wonder about the sort of questions that the empty uniform raises for other viewers?

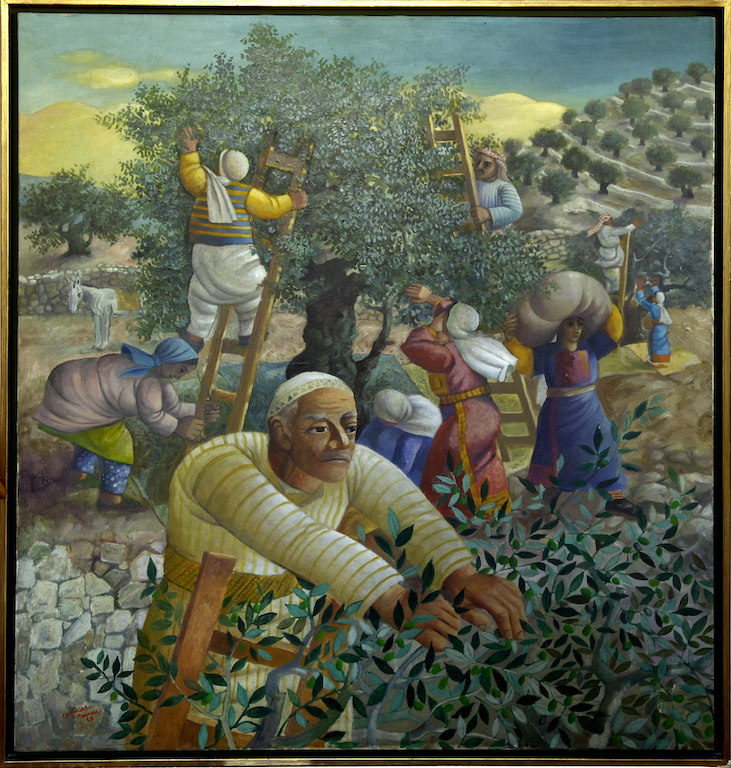

[Sliman Mansour, The Olive Harvest (1986). Image copyright the artist.]

[Sliman Mansour, The Olive Harvest (1986). Image copyright the artist.]

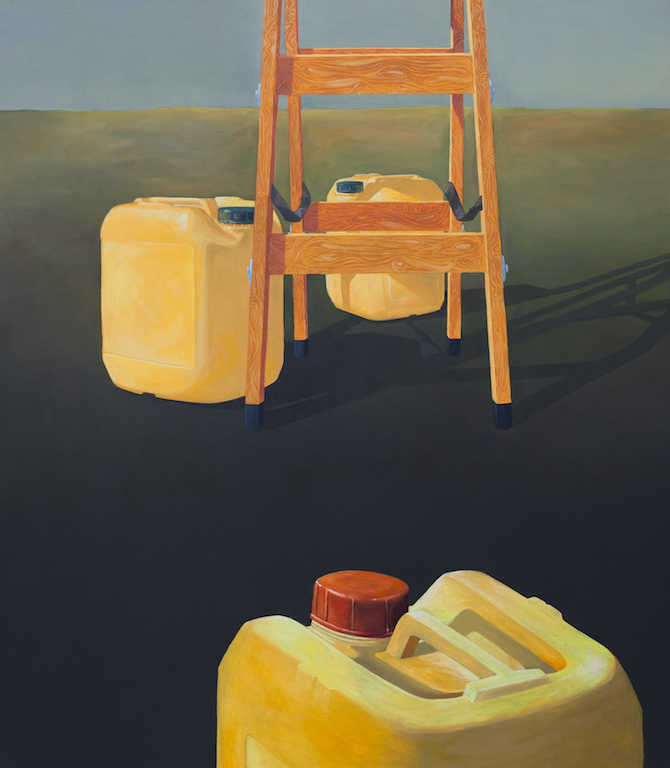

[Bashar Khalaf, The Olive Harvest (2016). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

[Bashar Khalaf, The Olive Harvest (2016). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

In one of Bashar’s Khalaf’s most direct references to the loss of land, and by extension, the loss of future for the Palestinians, he comments on Sliman Mansour’s ever-popular The Olive Harvest. In Khalaf’s 2016 version of The Olive Harvest, he positions in the middle of the canvas, the bottom section of a ladder that has been deployed in a desolate landscape. The top section of the ladder is cropped by the top of the composition, resulting in a visually compressed, inaccessible vertical space that conveys the feeling of being stuck. At the bottom of the ladder, Khalaf positions three large yellow jugs that are familiar to most Palestinians as the ubiquitous plastic containers used to hold the liquid “fruit” of the olive harvest. Unlike Sliman Mansour’s “Olive Harvest” where the lush foliage, gnarled trunk of the olive tree and peasants harvesting the olives, dominate the composition, the olive tree and the peasants have vanished in Khalaf’s landscape. The land is no longer fertile or prosperous, but has been reduced to a barren and desolate space that cannot support a population.

Additionally, the vantage point in Khalaf’s painting is completely different from Mansour’s depiction of the harvest. In Sliman Mansour’s painting, the body of the farmer picking the olives is surrounded by the branches and leaves of the olive tree. The peasant is not only in the tree, but is metaphorically part of its lush and bountiful canopy, suggesting the romantic nationalist trope, that the land and the people are one. The vantage point in Mansour’s painting places the viewer in the tree with the olive picker, making the viewer an active part of the timeless harvest ritual that has sustained Palestinians for millennia. With the disappearance of the olive tree in Bashar Khalaf’s painting and the depiction of the land as a barren wasteland, the cultural history and tradition of the olive harvest in Palestine appear to have been terminated. Even the product of that bountiful and timeless agricultural ritual has been reduced to a prepackaged commodity that can be bought from anywhere and sold to anyone.

Sliman Mansour and Bashar Khalaf’s fundamentally different depictions of The Olive Harvest reveal the connected, but dissimilar, realities of two distinct generations of Palestinians. Khalaf’s sobering depiction of the vanishing cultural ritual of the olive harvest, painted nearly thirty years after Mansour’s, identifies a devastating shift in the realities of the Palestinians’ relationship to their land. Khalaf’s painting acknowledges his generation’s increasing pessimism, by distinguishing the Palestinians’ current somber and cynical political attitude from the revolutionary optimism that was evident in the work of Sliman Mansour’s generation. Is Bashar Khalaf warning the viewer that the revolutionary spirits of active survival and creative resistance have died? That the land is gone? And that Israel’s ever expanding settler-colonial enterprise is succeeding in its goal to physically disconnect the indigenous Palestinians from the land and the land from the consciousness of the Palestinians?

Although my reading of Khalaf’s 2016 Olive Harvest is mournful, I think it is critical to carefully consider the sober, if not deeply pessimistic question that is being raised by his painting: has early Zionist propaganda (that the Jews were “returning” from their global diaspora to revitalize a promised land that remained barren and empty over the span of two-thousand years) been systematically shaped, through more than a century of lies, theft, forced displacement and cultural extermination, into an irreversible reality?

[Sliman Mansour, The Bearer of Burdens (1973). Image copyright the artist.]

[Sliman Mansour, The Bearer of Burdens (1973). Image copyright the artist.]

[Bashar Khalaf, The Bearer of Burdens (2015). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

[Bashar Khalaf, The Bearer of Burdens (2015). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

As one of the leading Palestinian visual artists, Sliman Mansour has created numerous iconic images that have served the cause of the Palestinian struggle. His work has influenced many, if not most, Palestinian artists. Mansour’s influence on Bashar Khalaf’s artwork is expressed with reverence, intelligence, and a high level of cultural critically that makes the series Shadow of the Shadow an engaging visual journey. The paintings are intelligent, well crafted, subtle, and most importantly timely, as they reflect the anxieties of a generation of Palestinians that have known nothing except a life under occupation.

Sliman Mansour’s best known and most widely reproduced painting The Bearer of Burdens (Jamel El Mohamel) depicts a barefooted peasant/laborer/refugee, straining under the weight of an oversized bundle that bears within it the old city of Jerusalem and the iconic Golden Dome. Mansour’s image speaks of the weight of memories, the burdens of history, the forced displacement of the Palestinians and the cruel denial of their right to return to their homeland. The painting suggests that although the refugees are physically disallowed from re-entering Palestine, the homeland is carried in the hearts and minds of millions of displaced Palestinians. Mansour’s “Bearer of Burdens” also reminds the viewer that Palestine’s history, customs and traditions have been passed on through the stories of the elders, from generation to generation of refugees. Mansour represents the massive bundle/burden, carried in silent dignity by the noble peasant/refugee, as a symbol of the lost homeland. The man’s oversized arms tirelessly hold on to the precious load, while his enormous legs and bare feet, worn and gnarled, like the trunk of an ancient olive tree, anchor him solidly to the ground. Mansour’s metaphorical image speaks of the refugees’ memories of a never forgotten homeland, and underscores their moral struggle to return. Sliman Mansour’s The Bearer of Burdens has been widely reproduced in the form of posters and postcard, and is still seen today in Palestinian refugee camps and homes throughout the world.

Bashar Khalaf took on a major challenge when he decided to re-interpret the cultural meaning of Sliman Mansour’s iconic image. In his 2015-2016 triptych, he created a metaphor that reflects his generations’ complex relationship to the refugees and to the burden of the denied homeland. Khalaf’s first decision in commenting on Mansour’s iconic image was to make three paintings instead of one, referencing the three versions of The Bearer of Burdens that Mansour painted. Khalaf completely altered the vantage point through which the viewer sees The Bearer of Burdens. He also changed the person bearing the burdens, made the metaphorical burdens invisible in the image, and created a deliberate ambiguity about the bearer’s relationship to the burdens and the homeland as depicted in Mansour’s original painting. In his dramatic alteration of Mansour’s visual narrative, Khalaf forces the viewer to ponder numerous uncomfortable questions about the impending disappearance of the land, the waning of memories, the fading of idealism, the seduction of materialism and the potential loss of national identity for a generation deluded by globalization. While Sliman Mansour’s The Bearer of Burdens identifies where the Palestinians came from, the ambiguity of Bashar Khalaf’s visual narrative leaves the viewer uncertain about where the Palestinians stand today and where they appear to be heading on a national odyssey that seems to offer no exit and no return.

[Sliman Mansour, Rituals Under Occupation (1989). Image copyright the artist.]

[Sliman Mansour, Rituals Under Occupation (1989). Image copyright the artist.]

.jpg) [Detail of Bashar Khalaf`s Rituals Under Occupation (2015-2016). Image copyright the aritst. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

[Detail of Bashar Khalaf`s Rituals Under Occupation (2015-2016). Image copyright the aritst. Courtesy of Gallery One, Palestine.]

Khalaf’s meditations on the political quagmire that the Palestinians find themselves in is directly addressed in his six-paneled painting depicting the flags of the six leading Palestinian political parties. Bashar Khalaf’s Rituals under Occupation was painted twenty-seven years after Sliman Mansour’s 1989 painting with the same title. While Mansour’s painting depicts revolutionary unity during the height of the First Intifada, Khalaf’s painting presents a very different reality of the Palestinians’ current political condition under occupation.

Khalaf’s painting employs the title of Mansour’s image as the starting point for a meditation on the dramatic differences between the revolutionary optimism of the late 1980s, and the frustrations and apathy that dominate today’s gloomy political horizon. Palestinian national resistance during the First Intifada was defined by decentralized grassroots actions, conducted by men and women working in creative unity against the occupation. By contrast, today’s divided and divisive political factions have fostered a culture shaped by disunity, ideological rigidity, physical as well as political fragmentation, and ineffectual resistance against the occupation.

In Mansour’s Rituals Under Occupation, a massive crowd carries a cross-shaped coffin that is draped in a Palestinian flag. The colors of the flag are mirrored in the colors of the shirts and headscarves of the men and women swarming together. Mansour included a self-portrait in the right foreground of the painting, suggesting that he was part of the revolutionary fervor. Amassed from individuals into a unified collective, the demonstrating crowd forms a forceful and endless river of people that stretches through the deep space of the painting. The crowd in Mansour’s painting moves as one body, shouts with one voice and acts in single-minded unity against the violence and oppression of the occupation. The proximity to the cross-shaped coffin of several women wearing the hijab, speaks of the religious, as well as the cultural and political unity of the Palestinians, during the First Intifada. Mansour’s depiction of Palestinian unity reminds me of the saying: “Before we are Muslims or Christians, we are first Palestinians. Before we are Fatah, or Hamas or PFLP, we are first Palestinians.”

Honest and compelling calls for unity between Palestinian factions are rarely heard today, and when they are spoken, a cynical population that has become deeply suspicious of its leaders, receives them with distrust. Khalaf’s six flags, individually depicted in front of a funerary black field and isolated from each other on six separate canvases, underscore the great dangers created by the debilitating divisions of contesting factions. The six isolated factional flags represent today’s divisive and adversarial Palestinian political landscape. In comparison to Mansour’s 1989 Rituals Under Occupation, Khalaf’s flags are presented as relics of a revolution that has become deeply fragmented and ideologically stagnant. The static and lifeless flags, physically and chromatically separated in Bashar’s six paneled painting, stand in strong contrast to Mansour’s depiction of the pulsating energy of Palestinian demonstrators that are culturally, politically and ideologically unified in their struggle, under a single national flag.

Competition amongst political factions can provide stimulating benefits as well as crippling hazards for a nascent nation struggling under the yoke of military occupation. By exacting much needed criticism, political competition can result in the creative advancement of a national agenda. However, the double-edged sword of competition can also deliver self-inflicted wounds that quickly fester and infect a nation with the maladies of division, jealousy, bitterness, ideological rigidity, and delusions of superiority. This is an especially dangerous phenomenon for a culture struggling under the violent manipulations of occupation, where the objectives of the occupiers thrive and are much more easily implemented when the occupied mistrust one another and are in constant conflict with each other.

By creatively re-imagining Sliman Mansour’s iconic nationalist paintings, Bashar Khalaf’s new series helps to identify the dangerous political terrain that the Palestinians find themselves in today. While wholly committed to the national struggle of the Palestinians, Khalaf’s sober paintings are devoid of Mansour’s romantic nationalism and revolutionary optimism. They serve as a mirror that critically reflects the menacing shadows darkening the horizon of the Palestinians’ precarious existential journey.

Editor’s note: Bashar Khalaf’s exhibition Shadow of the Shadow will be on view from 22 February to 31 March at Gallery One, Ramallah, Palestine.